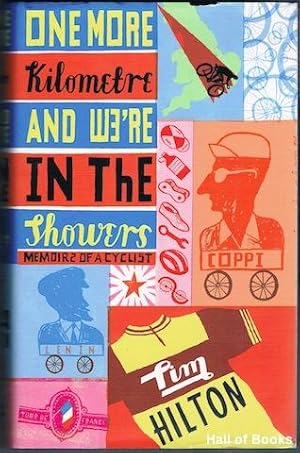

Tim Hilton’s

2004 cycling memoir, One More Kilometre

and We’re in the Showers, is my kind of cycling book. It’s a charming

account of Hilton’s cycling life in Britain in the second half of the twentieth

century, and it covers both his fan’s perspective of continental pro racing as

well as the history of Britain's unique club cycling and cycle-racing cultures.

Hilton’s background as an art critic (biographer of Ruskin), together with his communist

upbringing, gives him a unique perspective on this world. His delightful book

is literary (full of poetry and descriptions of club magazines from the 1950s

and 60s), nostalgic (celebrating the romance and mythology of English cycling’s

past), visual (an image accompanying each short chapter), and chock full of stories

that capture a time and place when cycling mattered in almost every town and village.

A good chunk

of the book (about a third) consists of a fan’s notes that recall the glories

of European pros Hilton followed closely as a young man in the 1950s and 60s: Coppi, Anquetil, Charly Gaul, Jean Robic,

Louison Bobet. Hilton recounts famous races, glorious battles, and tragic

demises of the greats, most of which he followed in French cycling magazines of

the day. Although I can see why Hilton wanted to include these stories, they

are, for me, the least interesting bits in the book; I’ve heard a lot of them

before, most many times. I get that this fandom of youth is an important part

of Hilton’s attachment to cycling, but a lot of these stories feel impersonal,

and I found myself skimming through these sections.

But the rest

of the book is a wonderful—a personal history of twentieth-century British cycling,

of a sort I’ve not encountered before. He

includes chapters on cycling magazines, fall hill rides, End-to-Enders, summer racing on grass tracks, 12-hour

rides, and new-to-me British cycling legends like Reg Harris, Brian Robinson, Beryl

Burton, and Eileen Sheridan.

One of my

favorite chapters is about Frank Patterson’s charming illustrations for Cycling magazine from 1893 to 1952,

which he produced under the pseudonym GHS. These simple drawings capture rural

or village scenes of ye olde England, always with a lone bicyclist pedalling

romantically along the laneway. As Hilton says, there’s something both lovely

and sad about these images of empty villages, reflecting a post-WWI age when

touring writers with lantern-slide images gave lectures on cycling adventures

but that also saw so many places lose all their men and boys in the trenches.

(The great irony, Hilton explains, is that Patterson, who created something

like 26 000 drawings for cycling magazines, was himself not a cyclist at all.)

Hilton also

reminisces fondly about the camaraderie and romance of mid-century club cycling,

with its Sunday runs and time trials, winter social events and club dinners.

The bond was intense among Dartford Wheelers, Tyneside Vagabonds, and

Colchester Rovers. As Hilton recalls, “Cyclists were said to have carried two

photographs with them during their active service: one of a wife or girlfriend,

the other of their club.” The brotherhood is strong in this cycling universe,

and not just among Hilton’s communist friends. He does talk about a few women

riders and even a women’s club (Rosslyn Ladies of the 1930s), but his kind of

social cycling was largely a boys’ club.

As Hilton

explains, the history of British cycle racing is unique because of its

anti-road-racing bias that lasted well beyond the middle of the twentieth

century. In the 1890s, the influential National Cyclists Union forbade the

running of mass-start races, which it deemed chaotic and detrimental to the

reputation of cycling in general. (In general, the NCU was big on touring, not

so big on racing.) That ban lasted for decades, and the dearth of road racing

lead to the development of vigorous track-racing and time-trialling traditions

in British cycling. (It’s worth noting that Hilton’s book pre-dated the rise of

Bradley Wiggins, Mark Cavendish, Chris Froome, and Team Sky, who’ve established

Britain as a road-racing power; in 2004, when this book appeared, the most

successful British road cyclists had been Tom Simpson and David Millar.)

Hilton makes

a compelling case for Sunday morning time trials as the English equivalent of

the Belgian kermesse: “English cycle

racing at its most basic level.” They happened early, 5:30 am, and there were

no spectators to cheer anyone on. “Nobody gives you a clap,” Hilton says, “since

bored girlfriends are sitting in cars, reading the newspaper.” Results were

posted on a bulletin board at the town hall. The whole thing was wrapped up

before most folks even got out of bed.

Time trials,

of course, are not so common in North America, and it took me a while to

understand just how central it has been to British cycling. In one of his more

eloquent moments, Hilton argues time-trialling is the purest form of cycling: a

rider alone with the bike, the road, and the clock. He explains: “There is

nothing like the feeling of riding a bicycle at maximum speed, at dawn, and

alone. Concentration becomes meditation—or something else, almost beyond

thought. It’s unlike anything else in the world of physical effort.”

When the

book first appeared in 2004, Hilton described the English cycling world, as he

knew it, as dying out. Club rides, time trials, point-to-point rides, and

12-hour rides remain important in some English towns, but, as he suggests, the

riders are getting older, with fewer and fewer youngsters taking up the sport.

I wonder if that’s changed at all since the success of Wiggo, Froome, and friends,

but even if there is a British cycling revival, I doubt it looks much like the world Hilton knew and loved.

I think I will add this to my Christmas reading list, Jasper!

ReplyDelete