In A Thread of English

Road (1924), American Charles S. Brooks, author of numerous forgotten

travel books and plays (including the strangely neglected Wappin’ Wharf: A Frightful Comedy of Pirates), travels quietly by bicycle

around villages of southern England, with two companions, rambling along the

back roads between London and Bath. Not much happens on the trip. They

encounter neither “high excitement” nor “raw adventure.” In fact, “Our days

were as tame as a kitten by the fire,” he admits on the second page. This

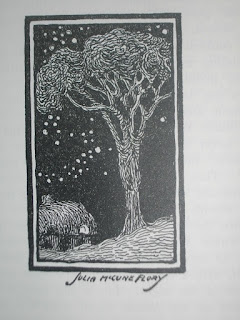

volume is more of a mood piece; Brooks’s prose and Julia McCune Flory’s

illustrations capture the quaint pace and gentle air of 1920s rural

England. Although at times the book feels a little too tame (some readers may wish for a frightful pirate or two), it has

its moments, stringing together some memorable beads on its “thread of

road.”

Brooks is fond of English village life and the English

countryside in the way that only a non-English city-man could be. (He was from Cleveland.) Hedges and

hearths, narrow streets, old doorways, country inns—these quaint, authentically

English details are what he’s after, and I suspect there was in the 1920s an

appetite in (urban) America for such vignettes of idyllic English village life,

which most Americans knew only from books, novels by Eliot and Hardy. For

Brooks, there’s a sense that most things English (except, perhaps, breakfasts)

are just–-better. English villages—the architecture, the characters,

the roads—just have more charm; even the dogs in England “are more civilized,

gentler than their cousins in America.”

A big part of the appeal of the book for me is Brooks’s

deeply literary bent. The book is as much a celebration of literature about English villages as about the villages themselves.

In fact, the volume is a late contribution to the popular nineteenth-century tradition

of literary pilgrimages, wherein bookish pilgrims set out to visit the

birthplaces, haunts, homes, and graveyards of famous writers, from Shakespeare

to the Brontes to Dickens and Hardy.

Interestingly, there is a cycling offshoot of this tradition

in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In fact, cycle-travel

accounts by the Pennells in the 1880s (in the footsteps of Chaucer, Stevenson,

and Sterne) and F.W. Bockett in 1901 (Jane Austen, Percy Shelley, Charles

Lamb), in particular, make a case for cycling as the ideal means for such literary

pilgrimages. Brooks is a kind of hybrid descendent of the two, combining the

American-literary perspective of the former with the eccentric style of the

latter.

The pages of are fairly studded with allusions to novels

about the English countryside. On page 14 alone Brooks makes reference to works

by Dickens, Fielding, Smollett, Sterne, and Richardson! So nerdishly literary

is Brooks that he indulges in a few clever-silly stylistic experiments that literary

geeks will appreciate. For instance, one amusing chapter is written in the

voice and manner of Samuel Pepys’s 17th-century diary. Another

alludes to Fielding’s playfully ironic chapters headings with the subtitle “A

Dull Chapter to Be Skipped.” (After a few pages, I did just that.)

While there’s little in the way of incident in the book, it

does offer oodles of style. Brooks knows his way around a sentence, and loves

to show off a playful sort of wit, which can occasionally veer into mauve, if

not purple, territory. He is the kind of deliberately old-fashioned writer who

sees no point in writing “sun” when “the eye of Phoebus” will do. But at times, he strikes an economically

poetic note, such as in this account of the end of a full and glorious day of

cycling: “And so to sleep! And I dreamed that I rode my bicycle seven times

around the moon and climbed a hill to find Orion at the top.”

For long stretches of this book, however, it’s easy to

forget that Brooks is travelling by bicycle at all. He goes for chapters at a stretch

without even mentioning his mode of travel. Then he’ll refer to the odd “tyre puncture”

or praise his new cycling “rain cape” (take note, Rivendell!) or report that an

innkeeper looked down his nose at their dusty “cycling tweeds.”

But he does make a point of noting, with wonder, that the

bicycle is still widely used in England unlike in America, where it was, by the

1920s, “on the dodo’s darkening path,” having been squeezed out by motorcars

much more completely than was ever the case in Europe. Brooks is excited to see

regular folks, carpenters and plumbers, riding their bikes to and from work,

“cheese and pie [hanging] upon the handle bars.” And he is astonished by the

sight of an “old gentleman in respectable silk hat pedaling a tricycle across

the country without blush or apology.” In America, he explains, only a child

would be caught riding such a contraption.

So while it may not be worth reading the book for “raw

adventure” or cycling content, I’d recommend picking it up for one other reason

alone: the terrific illustrations by Julia McCune Flory. As was the custom, the

illustrator Flory (and her husband, Walter, a Cleveland lawyer) accompanied

Brooks on his travels, making illustrations en route. Flory employs a thick,

often shaggy line in her simple, whimsical pen-and-ink sketches. They perfectly compliment

the quirky, nostalgic tone of Brooks’s writing while at the same time feeling

surprisingly modern somehow.

This is fitting, since A

Thread of English Road has an out-of-time quality; it feels like it could

have been written in 1904 or even 1884, rather than 1924. As Brooks himself

knew, there can be something timeless not just about an English village but also a book about English village life—even

if, maybe especially if, it’s written by an American.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Speak up!